Amarna Art Is a Term That Refers to Egyptian Art That Dates to the Reign of

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three daughters beneath the Aten, Berlin

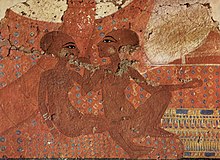

Two of Akhenaten's daughters, Nofernoferuaton and Nofernoferure, c. 1375–1358 BC. This comfortable and intimate family setting is repeated in other pieces of Amarna fine art

Princess of the Akhenaten family, Louvre

Amarna art, or the Amarna style, is a style adopted in the Amarna Menstruum during and only after the reign of Akhenaten (r. 1351–1334 BC) in the late Eighteenth Dynasty, during the New Kingdom. Whereas Ancient Egyptian fine art was famously slow to change, the Amarna fashion was a significant and sudden break from its predecessor both in the style of depictions, especially of people, and the subject thing. The artistic shift appears to be related to the king's religious reforms centering on the monotheistic or monolatric worship of the Aten, the disc of the Sun, as giver of life.

Like Akhenaten'due south religious reforms, his preferred art style was abandoned later on the end of his reign. By the reign of Tutankhamun, both the pre-Amarna religion and art mode had been restored.

Background and history [edit]

Before long after taking the throne, Amenhotep Four adopted a policy of religious reform centering on the Aten. While it is not clear if he held that the Aten was the just god (monotheism), he clearly regarded it every bit the only deity worthy of his worship (monolatry). To pay homage to his chosen god, Amenhotep Four inverse his proper name to Akhenaten.[one]

Throughout his dominion, Akenaten tried to change many aspects of Egyptian culture to celebrate or praise his god. He moved the majestic majuscule to the city now known as Amarna and erected a number of palaces and temples in that location. He besides extended his reforms to the style and usage of art.[2]

The end of the Amarna period is unclear, as records from the fourth dimension are sketchy. However, it is clear that around the beginning of the reign of Tutankhamun, about four years after Akhenaten's death, conservative forces led by the temple priests reimposed the former religion. The new uppercase was abandoned, and traces of his monuments elsewhere defaced. Remains of Amarna fine art are therefore concentrated in Amarna itself, with other remains at Karnak, where large reliefs in the way were dismantled, and the blocks turned round to face inwards when a afterwards building was synthetic using them. These were only rediscovered in recent decades.

General characteristics [edit]

Amarna art is characterized by a sense of movement and action in images, with figures having raised heads, many figures overlapping and many scenes busy and crowded. The man trunk is portrayed differently; figures, always shown in contour on reliefs, are slender, swaying, with exaggerated extremities. In particular, depictions of Akhenaten give him distinctly feminine qualities such as large hips, prominent breasts, and a larger stomach and thighs. Other pieces, such as the most famous of all Amarna works, the Nefertiti Bosom in Berlin, show much less pronounced features of the style.

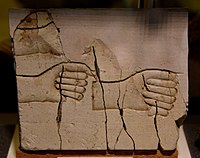

The illustration of figures' easily and feet are apparently of import. Fingers and toes are depicted as long and slender and are carefully detailed to testify nails. Artists also showed subjects with elongated facial structures accompanied by folds inside the skin also as lowered eyelids. The effigy was too illustrated with a more elongated body than the previous representation. In the new human form, the subject had more fatty in the stomach, thigh, and breast region, while the trunk, arm, and legs were thin and long similar the rest of the trunk.[three] The skin color of both male and female is generally dark dark-brown (contrasted with the usual dark brown or red for males and light brown or white for females). Figures in this style are shown with both a left and a right human foot, contrasting the traditional style of being shown with either two left or two right feet.

Art in the style [edit]

Tombs [edit]

The decoration of the tombs of non-royals is quite dissimilar from previous eras. These tombs exercise not feature whatever funerary or agricultural scenes, nor practice they include the tomb occupant unless he or she is depicted with a member of the royal family. There is an absenteeism of gods and goddesses, apart from the Aten, the sundisc. Nevertheless, the Aten does not shine its rays on the tomb possessor, merely on members of the royal family. There is neither a mention of Osiris nor other funerary figures. At that place is also no mention of a journey through the underworld. Instead, excerpts from the Hymn to the Aten are by and large present.

Akhenaten, Pharaoh of Egypt. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Sculpture [edit]

Sculptures from the Amarna period are set up autonomously from other periods of Egyptian art. I reason for this is the accentuation of sure features. For instance, the portrayals feature an elongation and narrowing of the cervix and head, sloping of the forehead and nose, a prominent chin, large ears and lips, spindle-similar artillery and calves, and large thighs, stomachs and hips.

In a relief of Akhenaten, he is portrayed in an intimate setting with his primary wife, Nefertiti, and their children, the 6 princesses. His children appear to be fully grown, only shrunken to appear smaller than their parents, a routine stylistic characteristic of traditional Egyptian art. They also have elongated necks and bodies. An unfinished caput of a princess from this time, in the Tutankhamun, and the gilded historic period of the pharaohs exhibition, displays a very prominent elongation to the back of the head.

The unusual, elongated skull shape often used in portrayal of the imperial family "may exist a slightly exaggerated treatment of a hereditary trait of the Amarna regal family", according to the Brooklyn Museum, given that "the mummy of Tutankhamun, presumed to exist related to Akhenaten, has a similarly shaped skull, although non so elongated every bit [in typical Amarna-manner art]". However, it is possible that the manner is purely ritualistic.

The hands at the end of each ray extending from Aten in the relief are delivering the ankh, which symbolized "life" in the Egyptian culture, to Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and often also reach the portrayed princesses. The importance of the Sun God Aten is central to much of the Amarna menstruation art, largely considering Akhenaten'south rule was marked by the monotheistic following of Aten.

In several sculptures of Akhenaten, if not most, he has wide hips and a visible paunch. His lips are thick, and his arms and legs are sparse and lack muscular tone, unlike his counterparts of other eras in Egyptian artwork. Some scholars suggest that the presentation of the human body equally imperfect during the Amarna period is in deference to Aten. Others remember Akhenaten suffered from a genetic disorder, nigh probable the product of inbreeding, that acquired him to look that way. Others interpret this unprecedented stylistic break from Egyptian tradition to be a reflection of the Amarna Royals' attempts to wrest political power from the traditional priesthood and bureaucratic authorities.

Much of the finest work, including the famous Nefertiti bust in Berlin, was establish in the studio of the 2d and terminal Royal Court Sculptor Thutmose, and is now in Berlin and Cairo, with some in the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, New York.

The period saw the use of sunk relief, previously used for large external reliefs, extended to small carvings, and used for most awe-inspiring reliefs. Sunk relief appears all-time in potent sunlight. This was one innovation that had a lasting effect, equally raised relief is rare in later periods.

Architecture [edit]

Non many buildings from this period accept survived the ravages of later kings, partially as they were constructed out of standard size blocks, known as talatat, which were very easy to remove and reuse. In recent decades, re-edifice work on afterward buildings has revealed large number of reused blocks from the menstruation, with the original carved faces turned inwards, greatly increasing the corporeality of piece of work known from the period.

Temples in Amarna did not follow the traditional Egyptian pattern. They were smaller, with sanctuaries open to the sun, containing large numbers of altars. They had no endmost doors. See Great Temple of the Aten, Small Temple of the Aten and the Temple of Amenhotep IV.

Gallery [edit]

-

Head of a daughter of Akhenaten. 18th Dynasty, c. 1345 BC. State Museum of Egyptian Fine art, Munich

-

Limestone trial piece showing head of Nefertiti. Mainly in ink, but the lips were cut out. Reign of Akhenaten, Amarna. Petrie Museum

-

Limestone trial piece showing the distinctive Amarna-style elongation of Akhenaten's face. Shallow sunk relief. Petrie Museum

-

Limestone trial piece of hands. Amarna, Reign of Akhenaten, late 18th Dynasty. Petrie Museum

-

Limestone trial slice of a private person. Head of a princess on the reverse. Reign of Akhenaten, Amarna. Petrie Museum

-

Princess, Amarna

See also [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amarna fine art. |

- Fine art of aboriginal Arab republic of egypt

- Amarna letters

References [edit]

- ^ Spence, Kate. "Akhenaten and the Amarna Period". bbc.co.uk . Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ Doyle, Noreen (September 2007). "Akhenaten'southward ART". Calliope . Retrieved October 27, 2015. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ Colina, Jenny. "Amarna Fine art". ancientegyptonline.co.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland . Retrieved September 27, 2015.

External links [edit]

- 'Gifts for the Gods: Images from Egyptian Temples, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on Amarna fine art

castellanoforeplarks.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amarna_art

0 Response to "Amarna Art Is a Term That Refers to Egyptian Art That Dates to the Reign of"

Post a Comment